Friday 16 March 2018

Everything is going to get worse and worse until you get rid of Assad

My contribution to a debate on Syria and the Left at SOAS on 15th March, 2018.

‘I spent a lot of time in 2013-14 unpacking the concept of intervention. Because you had an awful lot of people, especially on the left, whose entire discussion about Syria would be, “Well I’m not in favour of intervention,” and that would be simply the end of the conversation.

Partly it’s based on the war in Iraq. Believing that everything is about the war in Iraq. Which is partly an understandable carry forward from having your government lie to you. But is partly instrumentalised by people on the left, who say that was a great success for us, so if we cast everything in those terms, then that will mean everything else is a success for us. So if we say, anyone who says we should intervene in Syria is a right-wing warmonger, then we will be doing a good job for the left. Because we were proved right about Iraq, and you are all now Tony Blair.

What the intellectual versions of this would be, is to cast any sort of intervention as a full-scale invasion à la Iraq, so that you could steal their oil. Any sort of intervention was a slippery slope on the road to doing that, because that is what happened in Iraq. It was totally to ignore what was specific to Syria.

So much so that today you get people going, “Oh, Salisbury. Would the Russians really use chemical on people?” Because it’s in Britain it is more obvious that this is a complete pack of lies. This is where getting into the mindset of believing all these conspiracies gets you. But while it has been very successful in building a left alternative consensus in 2013, that what we needed to do was throw Syrians under the tank, and that was done because we’ve learned from experience tells us that staying out of wars is the way to solve them.

Whenever someone who had previously supported the war in Iraq proposed a solution. Then it would simply be read by what you would now call alt-left commentators as there is someone who wants to go and bomb Syria. Even if what they said was that we should have a No Fly Zone and support for the Free Syrian Army, and various other things that would try to avoid having Western boots on the ground as much as possible, it was simply, “Oh, you want to bomb Syria.” And that was the end of the debate.

Where Stop the War came in. They developed the belief after about 1991, that there was only one significant imperial power in the world, which was the US. And so everything they did was about saying what was bad was about the US. Even people who came from a tradition of saying Neither Washington Nor Moscow”, still, it’s everything is about the US. So when Russia invaded Georgia in 2009, the problem is that John McCain has been seen in Georgia, and they are going to try and oppress all these people and split up Russia. And we have to oppose all this.

Stop the War had organised lots of coaches for the Iraq War demo. And then they needed a reason to continue their existence. So they began to get funding because they were a voice opposing American power. And so that’s why they’ve been some of the worst people, because they’ve had a particular in saying this is all about America, this is all about stopping Britain from invading anywhere.

There are practical solutions that could have worked better five or six years ago. I think still the best way to go is to empower Syrians to fight against Assad.

I don’t think Syria is that complicated. I think it is essentially a question of Assad staying is such an immense destabilising force, that everything is going to get worse and worse until you get rid of Assad. You have to say what the critical debate is. There are other things you can do about solidarity. You can have solidarity with people under siege. But the fundamental debate about how you make things better, is about how you support Syrians to overthrow Assad, however difficult that looks at the moment.

I was going to try to avoid the whole Afrin question, because I am generally more positive about it than Leila is, but what can say about it is that there are now tens of thousands of trained Syrian fighters, fighting under the banner of the Free Syrian Army. Who once the operation is over, will want to see a free Syria that is liberated from Assad.

So while the forces that we would call the Free Syrian Army are now more dominated by foreign states than they ever have been, particularly Turkey, and that’s a problem, of self-determination, they do at least exist.

You can arm people with anti-aircraft weapons. That will stop the bombing. I remember the last time there was a debate about anti-aircraft weapons in relation to Aleppo, people said, “Oh yes, but MANPADS don’t work against the Russian bombers.” Well, that shouldn’t be the end of the debate then. Why can’t they get BUKs like the Russians are handing out like candy to their forces in the Ukraine to shoot down airliners with, and give them to Syrians to shoot down the Russian airforce? Or the US equivalent. Stinger missiles, whatever it is. Once you have decided the problem is Assad, that there is going to be no democracy, there is going to be no freedom of assembly, while he continues to rule, then the question is what are the practical ways you go about it.

I also think it is a situation in which you need all the forces fighting Assad to be fighting against Assad, and not fighting each other. There are Islamists who are more extreme than I would ever want to live under, and I’m not saying they should take over the place, but I am saying I don’t think these are the people the more secular forces should be fighting against. They should all be fighting against Assad.

It is a situation like the 1930s, where the Germans had a question of: you’ve got the Communist Party who are doing everything Stalin tells them, you’ve got the Social Democrats, who are selling out to Hitler in various ways, and selling out to capitalism, and so on. These people have to unite, in order to stop the fascists. And you can argue about what sort of society you create afterwards, but that’s sort of the brutal thing.’

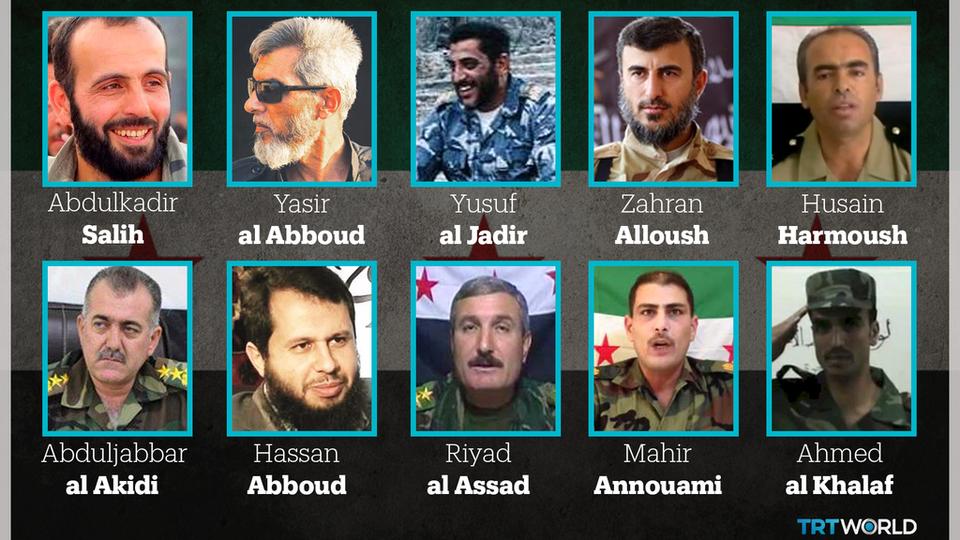

The Bravehearts of Syria

'Lieutenant colonel Yusuf al-Jadir made a strategic advance in one of the suburbs of Aleppo on December 15, 2012, destroying several tanks of Syrian regime leader Bashar al Assad.

One of his fighters asked him how he was feeling about the victory. Jadir said, “By God, I’m really sad. These tanks are our tanks, the ammunition [of the enemy] is ours, and the people we are fighting are our brothers. By God, I feel sad whenever one of us or them get killed. If that man [Assad] had resigned, Syria would have been one of the best countries in the world.”

Born in 1970 in the suburbs of eastern Aleppo, Jadir defected from Assad’s military in July 2012. Five months later, a few hours after gaining hold of an Aleppo suburb, he was killed in an air raid.

Jadir was among the most influential military officers who defected from the regime’s army in the summer of 2012. Though the “Free Syrian Army” was officially launched in July 2011, more and more soldiers joined the revolutionary ranks by 2012, a defining moment for tens of thousands of Syrians who protested against the Assad regime.

But seven years later, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) is no longer a well organised conglomerate of several fighting units. It is rather a deeply fragmented resistance movement that is spread across Syria, holding up key territories in Daraa, Idlib provinces, Aleppo suburbs and Ghouta, a Damascus suburb.

What happened between 2011 and 2017 is a story of Assad’s brutal military campaign aided by Russia and the culmination of several dozen fighting units backed by international players that changed the course of Syria’s revolution, pushing the country to a full-fledged civil war.

From 2012 onward, competing ideologies and interests caused cracks in the opposition. Some battalions and brigades started to form their own agendas beside toppling Assad.

To understand why the revolutionary forces were able to make strategic gains in the initial years, one must look into the lives of some of its key leaders. They were somehow able to bridge a gap between various fighting forces – whether they were “moderate”, “Islamists” or “patriotic.” And even today, the space they left seems to be unfilled. And until now, they are proving to be the irreplaceable leaders of the revolution.

Yusuf al Jadir defected from Assad’s army on July 18, 2012, and took the leadership role of Al Tawheed Brigade, one of the biggest armed oppositions in Aleppo. In its heyday, the brigade had at least 10,000 fighters.

Jadir participated in many battles against the regime forces north of Aleppo. He died in an air raid on December 15, 2012. Instead of harbouring the feelings of enmity, anger or revenge, Jadir looked after the welfare of hostages or the regime soldiers who surrendered in various battles. Many Syrians consider him as a national figure.

Jadir participated in many battles against the regime forces north of Aleppo. He died in an air raid on December 15, 2012. Instead of harbouring the feelings of enmity, anger or revenge, Jadir looked after the welfare of hostages or the regime soldiers who surrendered in various battles. Many Syrians consider him as a national figure.

Zahran Alloush wa born in 1971 in eastern Ghouta, Alloush came from a family of religious scholars. He studied in Saudi Arabia, where he finished his MA in Islamic Studies at the Islamic University.

He was known for being “moderate active Salafi,” a title that landed him in trouble. The regime arrested him for holding Salafist views in 2009.

Soon after the armed rebellion gained momentum, Assad released thousands of prisoners. Alloush was also set free. He was quick to gather fighters and form what he called the Islam Platoon, which gained several territories. He then named it the Army of Islam with more than 10,000 fighters under his belt.

Under Alloush’s military command, Daesh failed to impose its presence in eastern Ghouta. Alloush was against the extremist group, often referring to it as the “Baghdadi Gang”.

A few months before his death, foreign countries intervened against the revolutionary fighters, giving an advantage to the Assad regime, Alloush launched a key battle in Ghouta that enabled the opposition forces to get closest ever to Assad’s stronghold, Damascus.

But he was killed by a Russian air strike on December 25, 2015.

Known by his nickname “Hajji Mare,” Abdulkadir Salih was born in 1979 in Aleppo. Prior to the revolution, he used to be a grain merchant. As protests against Assad morphed into a nationwide uprising, Salih organised many demonstrations.

He was known for being “moderate active Salafi,” a title that landed him in trouble. The regime arrested him for holding Salafist views in 2009.

Soon after the armed rebellion gained momentum, Assad released thousands of prisoners. Alloush was also set free. He was quick to gather fighters and form what he called the Islam Platoon, which gained several territories. He then named it the Army of Islam with more than 10,000 fighters under his belt.

Under Alloush’s military command, Daesh failed to impose its presence in eastern Ghouta. Alloush was against the extremist group, often referring to it as the “Baghdadi Gang”.

A few months before his death, foreign countries intervened against the revolutionary fighters, giving an advantage to the Assad regime, Alloush launched a key battle in Ghouta that enabled the opposition forces to get closest ever to Assad’s stronghold, Damascus.

But he was killed by a Russian air strike on December 25, 2015.

Known by his nickname “Hajji Mare,” Abdulkadir Salih was born in 1979 in Aleppo. Prior to the revolution, he used to be a grain merchant. As protests against Assad morphed into a nationwide uprising, Salih organised many demonstrations.

Salih felt the urge to protect the people of Aleppo as the regime deployed brutal tactics to quell the uprising, often killing unarmed protesters, torturing and disappearing people. He joined the armed opposition and became one of the founding members of Al Tawheed Brigade, which succeeded in taking control of more than half of Aleppo.

Salih organised many rebel brigades in the region and was part of the FSA’s command structure.

He played a crucial role in bridging the gap between various opposition groups with different ideologies and schisms. His moderation was accepted by most of the fighting units in Aleppo and that alone led the regime to put a $200,000 bounty on his head, local experts say.

Salih survived at least two assassination attempts before he died on November 17, 2013, as a result of an air raid on the Infantry Academy of Al Muslimiyah north of Aleppo.

When some opposition fighters asked him about composing an anthem on his name, he said:

“If you want to write a song, do not mention my name, you could mention the name the Al Tawheed Brigade, the whole Muslim Nation, Syria, that is okay, however, don’t mention the name of a person. He might get arrogant."

So what changed after the revolution lost key leaders?

Aleppo’s largest Al Tawheed brigade collapsed soon after the death of Salih.

Rebel group Jaish ul Islam remained stuck in eastern Ghouta and never made any further advances after losing Zahran Alloush.

So far, no one has managed to replace them. Their charisma and ability to unite battalions and move away from the control of their funders made them indispensable.

Ahmad Abazzed, a military analyst from Daraa, said that the Assad regime had pinpointed these leaders and was desperate to eliminate them.

“Assad knew all the revolutionary forces were following the command of these charismatic leaders as they were from the first generation of rebels who fought against the regime,” Abazzed said.

It was clear, he added, that Assad’s and Russia’s first target was never Daesh or other extremist groups that killed in the name of religion, rather it was the FSA and other moderate opposition groups.

Though the strategy of bumping off top leaders worked with Al Tawheed and Jaish ul Islam, Abazzed said other battalions have learned to survive even after losing their main leaders.

“Because they have built an institutionalised structure and popular base among the masses.”

Moving forward, he said, the armed opposition has moved from building large military brigades to forming small and compact fighting units. “The new battalions that have been formed recently are easier to control than brigades that led the assault at the beginning of the revolution,” he said.

“I think regaining independence, strategic thinking, cultivating an understanding with various allies is important so that the opposition forces would be able to balance between the interests of the allies and the interests of the Syrian people.”

Abazzed said one thing was clear in the series of negotiations between the Assad regime and the opposition that took place in Geneva, Astana and Sochi. "The opposition should be able to represent Syria as a whole rather than representing local battalions or councils," he said. "Then only they can redefine themselves and stick to their main goal to topple Assad first.” '

Aleppo’s largest Al Tawheed brigade collapsed soon after the death of Salih.

Rebel group Jaish ul Islam remained stuck in eastern Ghouta and never made any further advances after losing Zahran Alloush.

So far, no one has managed to replace them. Their charisma and ability to unite battalions and move away from the control of their funders made them indispensable.

Ahmad Abazzed, a military analyst from Daraa, said that the Assad regime had pinpointed these leaders and was desperate to eliminate them.

“Assad knew all the revolutionary forces were following the command of these charismatic leaders as they were from the first generation of rebels who fought against the regime,” Abazzed said.

It was clear, he added, that Assad’s and Russia’s first target was never Daesh or other extremist groups that killed in the name of religion, rather it was the FSA and other moderate opposition groups.

Though the strategy of bumping off top leaders worked with Al Tawheed and Jaish ul Islam, Abazzed said other battalions have learned to survive even after losing their main leaders.

“Because they have built an institutionalised structure and popular base among the masses.”

Moving forward, he said, the armed opposition has moved from building large military brigades to forming small and compact fighting units. “The new battalions that have been formed recently are easier to control than brigades that led the assault at the beginning of the revolution,” he said.

“I think regaining independence, strategic thinking, cultivating an understanding with various allies is important so that the opposition forces would be able to balance between the interests of the allies and the interests of the Syrian people.”

Abazzed said one thing was clear in the series of negotiations between the Assad regime and the opposition that took place in Geneva, Astana and Sochi. "The opposition should be able to represent Syria as a whole rather than representing local battalions or councils," he said. "Then only they can redefine themselves and stick to their main goal to topple Assad first.” '

Thursday 15 March 2018

Syria Is In No Civil War

'Having now completed its seventh year, the Syrian conflict, one of the deadliest humanitarian crises of our time, continues to be characterized as a civil war.

Such a categorization, however, is both inaccurate and troubling, as it simplifies a very complicated situation.

It allows us to become disillusioned with the idea that problems “over there” are just that and have no impact elsewhere, resulting in a collective numbness and shrugging-of-shoulders when images of war-torn Syrian cities and towns (too rarely) dominate our front pages.

Such a simplification is dangerous.

It exonerates the international community of responsibility, producing global apathy. It allows internal and external groups to justify their involvement and use of violence, fails to acknowledge the direct and active role of powerful players like Russia and Iran, and gives Syrian president Bashar al-Assad a facade of legitimacy by equating the killer with the victims.

In March 2011, following decades of stagnation and oppression, a sudden awakening of a disenchanted Syrian populace – one which had lost patience with a failing, anocratic state – swept through the nation when a group of teenagers were arrested and tortured in the southwestern Syrian city of Daraa for painting graffiti featuring messages in support of the Arab uprisings.

Daraa’s consequent rallying cry for the release of the boys was met with a ferocious crackdown of security forces, who reverted to the logic of violence by killing and detaining innocent civilians.

Struggles for freedom, economic woes, and public anger over harsh government retaliation resulted in a shift in chants from local and reformist demands, to a call for the complete overthrow of the Assad regime.

Further, the toppling of the Tunisian and Egyptian regimes fuelled hope among Syrian protesters, who continued risking their lives demanding dignity (karama), liberty (hurriyya), and revolution (thawra).

Armed resistance against the Assad regime grew in the form of self-defence as soldiers began defecting from the Syrian military via YouTube videos following the summer of 2011. This led to the birth of the Free Syrian Army, marking the weaponization of the conflict.

There are local factions that fight against one another from time to time – still, the underlying power dynamic between the regime and the Syrian people is one that is too convoluted to be characterized as a civil war.

We see this in the arbitrary violence perpetrated by the Assad regime against a helpless populace.

Soldiers were forced to shoot unarmed demonstrators or were shot themselves. Stadiums and school classrooms were turned into prison camps where mutilation and torture of the worst kinds imaginable were inflicted on men, women, and children, including the elderly and wounded. Public rape, forced starvation, aid obstruction, and indiscriminate executions were used as instruments of warfare and deterrence.

This degree of atrocities deployed against a largely unarmed population failed to suppress rebellion. The regime’s survival strategy – one of oppressive tactics and its attempt to blame sectarian divisions and foreign conspiracies for the violence – proved ineffective.

And so, in a deliberate attempt to aggravate the conflict and radicalize what remained of formerly peaceful demonstrations, Assad released dangerous extremists from prison – a number of whom now compose the majority of ISIS leadership. This has helped him shift the narrative, emphasizing so-called Islamic terrorism as a key characteristic of the conflict, thereby presenting himself as a partner in the global war on terror and justifying his use of violence.

How can we refer to the conflict as a civil war, given the vast amount of external interference?

Foreign powers have prioritized violence and significantly exacerbated the conflict.

Following the outbreak of demonstrations in 2011, Shiite fighters from Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran were immediately deployed in Syria to support the Assad regime.

Moscow has also been integral to Assad’s survival. Since 2015, Russia has been launching airstrikes targeted at Syrian rebel forces, which often entails targeting Syrian neighbourhoods, hospitals, and schools.

The most brutal bombardments are currently being carried out by pro-government forces in eastern Ghouta, an agricultural, rebel-held enclave located in the northern Damascene countryside that has been under siege since 2013 and is home to an estimated 400,000 civilians. Since mid-November, over 1,200 air strikes and more than 6,000 rockets and shells – some of which have reportedly contained chlorine gas – have been fired at the enclave. This is despite the fact that eastern Ghouta was declared a “de-escalation zone” last May; that is, the region is under a diplomatic ceasefire agreed to by Russia, Iran, and Turkey.

The death toll in eastern Ghouta continues to rise. In a one-week period earlier this year, the number of casualties exceeded 500, with thousands of civilians severely injured. Relentless air and artillery strikes have forced civilians to seek shelter underground and has left the region largely deprived of medical care, foodstuffs, sanitation, and other basic necessities.

The conflict has produced well over five million refugees and six million have been internally displaced – more than half of the country’s pre-war population. More than eight million children have been affected by the conflict and over 13 million Syrians are in need of immediate humanitarian assistance. Nearly half a million people have been killed, more than two million injured, and more than 65,000 have disappeared in Syria’s torture prisons.

This is a war carried out by Assad and his foreign allies against the people of Syria, a murderous campaign to exterminate a nation in order to maintain a long-standing power dynamic in the region.

Do not equate the killer with the victim.

This is not a civil war.'

Monday 12 March 2018

Assad’s rape victims break their silence

Yvonne Ridley:

'The torture victim stood in front of her tormentor wondering what treatment would be meted out this time in the notorious Branch 215, also known as Raid Brigade run by military intelligence in Damascus. Would it be a merciless beating or would it be another sex assault on her already broken body?

The start of the investigation was interrupted suddenly by a ringing telephone and she watched and listened with incredulity as the voice laughing and giggling down the line prompted the torturer to break into a warm smile. Almost automatically, he softened the tone of his voice, for that is the effect most daughters have on their fathers.

In the seconds that he looked away from his torture victim he had morphed from brutal monster into a warm and caring father. This was one of the more chilling aspects that emerged from the stories I heard from Syrian women who have been swept up on an industrial scale and thrown into Bashar Al-Assad’s prisons since the start of the 2011 war. The cold reality is that the mass rapes, sexual assaults, punishment beatings and mental torture are being inflicted on women routinely by someone else’s fathers, husbands and even grandfathers.

At the end of the shift, these men must return to their family homes and normality, having completely destroyed the lives and souls of the women and young girls in their grip. The harsh reality is that if your husband works in Branch 215 then he is probably a serial rapist or is standing by as a spectator watching the most heinous, unimaginable crimes being carried out on women prisoners and girls.

I wonder how this particular monster responded when he got home and was asked, “What did you do today, Daddy?” Obviously he would not be telling his daughter about the teeth he smashed, the bones he had broken or the sex he had forced on his victims.

While trying to shine a light on this dark underbelly of the Assad regime, I met several women who ended up in Branch 215 or other equally terrifying prisons and ghost jails run by the Syrian regime. In every encounter, the image of Bashar Al-Assad loomed large, either in portraits hanging on walls or on the T-shirts worn by the men responsible for the brutal rapes.

Yes, you read that accurately. Incredible as it may seem, the face of the Syrian leader is emblazoned on T-shirts worn by the rapists in his employ, as if he defiles Syrian women by proxy. No wonder that many who manage to get out of the prisons cannot bear to look at the face of the Syrian leader. Those small, thin lips and piercing stare must send shivers down their spines every time they see his image.

“Some days I manage to forget what happened to me,” Noor told me, “and then suddenly I’ll see someone sneer or curl their lip in a certain way and it acts like a trigger; I’m back inside 215 suffering from a flashback, feeling terror and anxiety.” Three years on from her own ordeal she puts on a good face for the outside world but you just know, in her darker moments, that she’s plunged back into the stuff of nightmares.

The start of the investigation was interrupted suddenly by a ringing telephone and she watched and listened with incredulity as the voice laughing and giggling down the line prompted the torturer to break into a warm smile. Almost automatically, he softened the tone of his voice, for that is the effect most daughters have on their fathers.

In the seconds that he looked away from his torture victim he had morphed from brutal monster into a warm and caring father. This was one of the more chilling aspects that emerged from the stories I heard from Syrian women who have been swept up on an industrial scale and thrown into Bashar Al-Assad’s prisons since the start of the 2011 war. The cold reality is that the mass rapes, sexual assaults, punishment beatings and mental torture are being inflicted on women routinely by someone else’s fathers, husbands and even grandfathers.

At the end of the shift, these men must return to their family homes and normality, having completely destroyed the lives and souls of the women and young girls in their grip. The harsh reality is that if your husband works in Branch 215 then he is probably a serial rapist or is standing by as a spectator watching the most heinous, unimaginable crimes being carried out on women prisoners and girls.

I wonder how this particular monster responded when he got home and was asked, “What did you do today, Daddy?” Obviously he would not be telling his daughter about the teeth he smashed, the bones he had broken or the sex he had forced on his victims.

While trying to shine a light on this dark underbelly of the Assad regime, I met several women who ended up in Branch 215 or other equally terrifying prisons and ghost jails run by the Syrian regime. In every encounter, the image of Bashar Al-Assad loomed large, either in portraits hanging on walls or on the T-shirts worn by the men responsible for the brutal rapes.

Yes, you read that accurately. Incredible as it may seem, the face of the Syrian leader is emblazoned on T-shirts worn by the rapists in his employ, as if he defiles Syrian women by proxy. No wonder that many who manage to get out of the prisons cannot bear to look at the face of the Syrian leader. Those small, thin lips and piercing stare must send shivers down their spines every time they see his image.

“Some days I manage to forget what happened to me,” Noor told me, “and then suddenly I’ll see someone sneer or curl their lip in a certain way and it acts like a trigger; I’m back inside 215 suffering from a flashback, feeling terror and anxiety.” Three years on from her own ordeal she puts on a good face for the outside world but you just know, in her darker moments, that she’s plunged back into the stuff of nightmares.

Badria is not as fortunate; for her, the nightmare continues five years after she and 40 women in Homs were rounded up and taken to an apartment in the Syrian revolution’s fallen capital. When she was arrested she was dressed in black and wore a full face veil, which made her more of a target for her Alawite captors who taunted, mocked and abused her for her piety.

Once the captors had left the large, spartan room she began to perform tayammum using the stone floor because normal wudu — the Islamic ritual of washing before prayer – was impossible. Unknown to her, CCTV cameras caught her actions and as soon as she tried to prepare for Salah the men returned and beat her with sticks.

She had her feet and wrists bound and was left hanging from a ceiling hook by the rope around her hands. Every time she mentioned the name of God or any Islamic reference she was beaten. Hands shaking, she looked at me and opened her mouth slowly before removing her dentures. Her teeth, top and bottom, had been shattered by the sticks swung hard and with deliberate precision across her face. Her cheekbones were fractured.

“I used to have full breasts,” she said as she lifted her shirt, “but now look.” Doctors have told her that the beatings across her breasts were so severe that the tissue was destroyed and will probably never recover. In terms of dress size she was probably an English 14, medium to large when she was arrested, but as she sat before me she looked more like a Size 6, a skeleton draped in skin which will bear the scars of captivity for life.

Speaking through a translator, she told me how the women in her group were taken into a smaller room where they were raped and humiliated by two or more of the military intelligence officers. There, above the bed, staring down, were portraits of Assad and his brother Maher. To the side of the bed was a small table with various bottles of alcohol for the men to drink.

To combat their drunken state, explained Badria, they took blue pills before forcing themselves on their prey. She also described how some would put an orange pill under their tongue. After some research I concluded that the drugs she described were the blue diamond-shaped Viagra and the orange pill Levitra, which works four times faster in some men, taking effect after just 15 minutes.

There was no need to ask Badria if she had been sexually assaulted; the detail she provided about the inside of the rape room, the pills and the alcohol, and the portraits of the Assad brothers leering down told me all I needed to know. She had been forced into the room on numerous occasions where cameras were also installed and the women were led to believe that their images and photographs had been taken.

She told me of one woman who was “gang raped to death” while another had simply lost her mind. Freedom for Badria came at a price; $17,000 was the ransom paid by her family to get her out of prison. If she thought the nightmare would end then, though, she was wrong. Her husband did not survive the military prison in Homs where he was held; witnesses told her that he died after having his eyes gouged out by his captors.

Her father and one of her brothers were martyred fighting in the Free Syrian Army and the brother who borrowed so heavily to get her released is now in prison himself, being unable to repay the debt. Meanwhile her sister has been arrested and locked up, and those left in the family are trying desperately to raise the $1,000 being demanded for her release. So not only is the Assad regime abusing women on an industrial scale, but it is also making money out of their misery and running what amounts to a sordid slave trade.

Badria’s son, aged around seven, sat in silence as his mother told her story; every now and again, when the details became too graphic, she sent him on an errand. He looked nearly as traumatised as his mother who was shrinking before his eyes in stature and health. She looked so frail as I got up to leave, that it was difficult to give her a sisterly hug; I honestly felt that she might snap.

Once the captors had left the large, spartan room she began to perform tayammum using the stone floor because normal wudu — the Islamic ritual of washing before prayer – was impossible. Unknown to her, CCTV cameras caught her actions and as soon as she tried to prepare for Salah the men returned and beat her with sticks.

She had her feet and wrists bound and was left hanging from a ceiling hook by the rope around her hands. Every time she mentioned the name of God or any Islamic reference she was beaten. Hands shaking, she looked at me and opened her mouth slowly before removing her dentures. Her teeth, top and bottom, had been shattered by the sticks swung hard and with deliberate precision across her face. Her cheekbones were fractured.

“I used to have full breasts,” she said as she lifted her shirt, “but now look.” Doctors have told her that the beatings across her breasts were so severe that the tissue was destroyed and will probably never recover. In terms of dress size she was probably an English 14, medium to large when she was arrested, but as she sat before me she looked more like a Size 6, a skeleton draped in skin which will bear the scars of captivity for life.

Speaking through a translator, she told me how the women in her group were taken into a smaller room where they were raped and humiliated by two or more of the military intelligence officers. There, above the bed, staring down, were portraits of Assad and his brother Maher. To the side of the bed was a small table with various bottles of alcohol for the men to drink.

To combat their drunken state, explained Badria, they took blue pills before forcing themselves on their prey. She also described how some would put an orange pill under their tongue. After some research I concluded that the drugs she described were the blue diamond-shaped Viagra and the orange pill Levitra, which works four times faster in some men, taking effect after just 15 minutes.

There was no need to ask Badria if she had been sexually assaulted; the detail she provided about the inside of the rape room, the pills and the alcohol, and the portraits of the Assad brothers leering down told me all I needed to know. She had been forced into the room on numerous occasions where cameras were also installed and the women were led to believe that their images and photographs had been taken.

She told me of one woman who was “gang raped to death” while another had simply lost her mind. Freedom for Badria came at a price; $17,000 was the ransom paid by her family to get her out of prison. If she thought the nightmare would end then, though, she was wrong. Her husband did not survive the military prison in Homs where he was held; witnesses told her that he died after having his eyes gouged out by his captors.

Her father and one of her brothers were martyred fighting in the Free Syrian Army and the brother who borrowed so heavily to get her released is now in prison himself, being unable to repay the debt. Meanwhile her sister has been arrested and locked up, and those left in the family are trying desperately to raise the $1,000 being demanded for her release. So not only is the Assad regime abusing women on an industrial scale, but it is also making money out of their misery and running what amounts to a sordid slave trade.

Badria’s son, aged around seven, sat in silence as his mother told her story; every now and again, when the details became too graphic, she sent him on an errand. He looked nearly as traumatised as his mother who was shrinking before his eyes in stature and health. She looked so frail as I got up to leave, that it was difficult to give her a sisterly hug; I honestly felt that she might snap.

At another house I was taken to I met a mother-of-five called Aishah who was arrested in the early days of the war because she had taken part in the street demonstrations. She was taken to Branch 215 where she was beaten “in a humiliating manner”. She was moved around the intelligence system and taken to three other branches, including one at Adra.

During her incarceration she saw girls as young as seven, old women and every age in between detained, raped and abused. She spoke of the five military officers who put on T-shirts bearing the portrait of Assad before carrying out their gang rape on one woman. “They declared Assad to be their god,” she said.

Now living safely on the Turkish border near Hatay with her five girls aged three to 17, Aishah is widowed. Her husband, who was also arrested and abused, survived his prison ordeal only to be killed in an air raid in eastern Ghouta three years ago just after the birth of his fifth child.

The women I met all want justice. They want to see the men who tortured, raped and abused them stand trial for the war crimes that they have all undoubtedly committed. I’d like to be able to report that they are now safe and secure but I’m not sure that they will ever be able to recover fully. One told me that the moment she closes her eyes she’s back inside the hellish prison, waiting for Assad’s men to pounce.

What makes this all so much worse is that there are believed to be around 7,000 women and 400 children still inside the Syrian regime’s jails. That is what last week’s Conscience Convoy to the Turkey-Syria border was all about; 10,000 women from 55 nations assembled to demand the release of the prisoners.

I don’t care if it takes money to get them out of the grip of these monsters, but having spoken to the victims, I know for certain that Assad can never be part of the solution in Syria. In more than 40 years as a journalist, I’ve interviewed prisoners from Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Bagram in Afghanistan, Guantanamo, Abu Saleem in Tripoli and Toulal 2 Prison in Meknes, Morocco, but I have never encountered evidence of so much depravity and inhuman behaviour on such a large scale as what is unfolding right now — even as you read this — in Assad’s prisons.

There is a brutal regime in Damascus, run by monsters who masquerade as doting husbands and family men in homes around Syria while carrying out of the most horrendous crimes. “What did Daddy do at work today?” Trust me, you don’t want to know, habibi; Daddy and his monstrous associates have to be stopped.'

During her incarceration she saw girls as young as seven, old women and every age in between detained, raped and abused. She spoke of the five military officers who put on T-shirts bearing the portrait of Assad before carrying out their gang rape on one woman. “They declared Assad to be their god,” she said.

Now living safely on the Turkish border near Hatay with her five girls aged three to 17, Aishah is widowed. Her husband, who was also arrested and abused, survived his prison ordeal only to be killed in an air raid in eastern Ghouta three years ago just after the birth of his fifth child.

The women I met all want justice. They want to see the men who tortured, raped and abused them stand trial for the war crimes that they have all undoubtedly committed. I’d like to be able to report that they are now safe and secure but I’m not sure that they will ever be able to recover fully. One told me that the moment she closes her eyes she’s back inside the hellish prison, waiting for Assad’s men to pounce.

What makes this all so much worse is that there are believed to be around 7,000 women and 400 children still inside the Syrian regime’s jails. That is what last week’s Conscience Convoy to the Turkey-Syria border was all about; 10,000 women from 55 nations assembled to demand the release of the prisoners.

I don’t care if it takes money to get them out of the grip of these monsters, but having spoken to the victims, I know for certain that Assad can never be part of the solution in Syria. In more than 40 years as a journalist, I’ve interviewed prisoners from Abu Ghraib in Iraq, Bagram in Afghanistan, Guantanamo, Abu Saleem in Tripoli and Toulal 2 Prison in Meknes, Morocco, but I have never encountered evidence of so much depravity and inhuman behaviour on such a large scale as what is unfolding right now — even as you read this — in Assad’s prisons.

There is a brutal regime in Damascus, run by monsters who masquerade as doting husbands and family men in homes around Syria while carrying out of the most horrendous crimes. “What did Daddy do at work today?” Trust me, you don’t want to know, habibi; Daddy and his monstrous associates have to be stopped.'

Sunday 11 March 2018

A Kurdish couple's love blossoms under Assad's torture

'On the afternoon of February 12, a Kurdish family of four from northern Syria broke into an old Kurdish song. “Once upon a time there was a girl from Afrin, whose heart was broken...,” they sang in unison.

Azad Osman, his wife, son and daughter sat in the living room of their apartment in a poor suburb of southern Turkey’s Mersin province. With his head down, the 53-year-old Osman followed the notes of the Turkish saz, its chords struck by Dilar, his son.

For a moment, the family seemed to have drifted away from all their worries, away from morbid memories of war and trauma. But as they finished singing, they were back to reality.

They are refugees who have not only survived the deadly bombings of the Assad regime, but also endured the abuse and trauma inflicted by the YPG, an armed extension of the PKK, which is considered as a terrorist organisation by the US, EU and Turkey.

Both Osman and his wife, Sefira Sido, had been punished for espousing the communist cause since their youthful days. Their union began at the University of Aleppo, while at a protest against the dictatorial policies of Syria’s former president Hafez al Assad in 1987.

First, intelligence officers arrested Osman on campus, then they picked up Sido from the nearby nursing college, where she was pursuing her diploma in paramedical sciences.

“They (the intelligence police) took me to different places and then they finally led me into a small room where Azad was held,” she said.

She saw Osman naked, handcuffed to the ceiling.

“They asked me, 'how do you know each other,’” Sido recalls. “I told them, ‘I love him.’”

She was moved to a women’s prison cell, where she spent 15 days before her release. Osman was released soon after. But they were both blacklisted. And they were dismissed from their schools and all government-run avenues were closed for them.

Though they have grown disillusioned with the communist cause, their love for each other is resolute. When Sido speaks about Osman, her eyes still light up with joy and she often tells him 'hezdikim', 'I love you' in Kurdish.

Born in 1965 in Aleppo, Osman grew up in a politically active family. Though his father was a peasant who struggled to make a living, he was affiliated with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), a political front currently led by Masoud Barzani in northern Iraq.

In the 1960s, Osman’s father worked for the front’s branch in northern Syria. Barzani's father, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, led armed assaults against the then-governing Baath party in Iraq. He also spoke critically of the party’s extension in Syria led by former president Hafez al Assad.

The Baathist regime in Syria perceived Barzani’s KDP as a threat, frequently launching military crackdowns against its members in Syria.

Since Osman’s father was a frequent target of those crackdowns, Osman did not have a happy childhood. “When I was about six or seven years old, my mother woke me up. I got up to see my father being taken away. They were hitting him and dragging him,” Osman said.

“It was very difficult and hard, my father was being hit and dragged right in front of my eyes. Time passed; I grew up. But what I witnessed then stayed with me.”

In his early 20s, Osman became a member of the Syrian Communist Party, which was founded by a Syrian Kurd named Halit Bektas. The party underwent a split in 1986 and ideological differences emerged within various communist networks in the country. But Osman stayed loyal to the communist cause for almost 24 years.

But in 2004, he couldn’t relate to the communist movement anymore, although he was smouldering with the revolutionary sentiment.

Osman came to believe that communist parties in Syria had been hijacked by the state. His longtime comrade Mustafa Ali Mousto said that it took them a few years to understand that some of the leftist groups in the country had grown "under the wings of Assad’s Baathist regime.”

By the mid 1990s, Osman formed a civil society group to moderate discussions on democracy among the Syrian people. He cultivated friendships among the “like-minded” Kurds, who shared similar grievances against the Baathist regime, and the PKK and its proxies.

His drive to build up a strong opposition took him to Iraq, where he reached out to anti-Baathist networks. By the early 2000s, he had developed strong ties with “several small groups” in Sulaymaniyah, a predominantly Kurdish city in northern Iraq. He discreetly hosted meetings, introducing prominent Kurdish community leaders who held anti-Baathist and anti-PKK views, in Sulaymaniyah, Erbil, Aleppo and Damascus.

Around the same time, he also set up a food company in Sulaymaniyah. But he couldn’t dodge Assad’s shadow state for too long. He was arrested in 2007 for conspiring against the regime, a charge that was commonly slapped on people for speaking against Assad.

Unlike his previous detention, which lasted for two weeks, this one was much longer. He was imprisoned in the notorious Sednaya Prison, which is known as “Assad’s slaughterhouse," where 13,000 people have been secretly hanged by the Syrian regime, according to Amnesty International.

His fellow prison inmates held differing political views. They were largely affiliated with Al Qaeda and the PYD, the PKK’s political extension in Syria.

At times, fist fights would break out over political disagreements. Osman managed to survive the toxic prison environment. One thing always kept eating at him from the inside though: his longing for his wife Sido.

For two and a half years she was denied a jail visit to Osman. When she was finally allowed to see her husband, she could not speak at all. “She just kept crying,” Osman said.

Osman befriended several inmates who somehow shared a similar worldview and they all aspired for a revolution. The revolution did happen, but it did not happen in Syria. In 2011, the wave of the protests, dubbed Arab Spring, swept Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, pushing long-serving dictators out of power.

“We were happy to hear that and we hoped it will come to our country too,” Azad said. “We had debates in the prison, some of my friends would say that the regime is too strong, fascist and indestructible. But I held the opposite view saying that the Spring would come to Syria anyway.”

By March 2011, tens of thousands of Syrians were inspired by the Arab Spring. They took to the streets, demanding the resignation of Bashar al Assad.

But the regime retaliated with brute force, killing hundreds of protesters, raiding towns and villages to quell the uprising. In retaliation, the Syrian people were compelled to take up arms to save themselves from Assad’s military, which was baying for blood. The hopes of Osman and his inmates to see a peaceful Syrian revolution succeed were soon dashed as the country slipped into a civil war.

As the armed opposition made some territorial gains, Osman said, the Assad regime opened its prison gates, releasing several hundred members of Al Qaeda and the YPG/PKK.

At the same time, Assad’s security forces withdrew from predominantly Kurdish-populated northern Syria, leaving the YPG as an essential force there.

The idea behind releasing the dreaded militants—accused of horrendous terror acts—was to open several fronts and divide the opposition along ideological lines.

Osman was released along with hordes of other prisoners.

The amnesty was a calculated move. It opened a new macabre chapter of deaths and destruction in Syria. The armed revolution, that was recognised by global powers like the US, the UK and Turkey, was undermined as members of Al Qaeda, released by Assad, and other extremists groups started to mobilise, recruiting foreign fighters and raising money from the Gulf countries. Amidst the wave of extremism, Daesh emerged as another force, besides Al Qaeda-backed fronts like Al Nusra.

“They aimed to spoil Syrian revolution by releasing those militants,” Osman said. “They soon assumed leadership positions in Al Nusra and Daesh.”

“They (the Gulf monarchs) spread fear among their population by giving them an example of Syria. They said, 'If you want democracy, look at Syria,'” Osman said. “Even Nigeria's government used Syria’s example to bring its population under control. In the end, Syria was sacrificed.”

On the other hand, Assad held his fort in Damascus with the help of Russia and Iran. While Russia provided military support to Assad, Iran sent its Shia militias to fight the revolutionary forces.

Osman picked up arms in 2012. “We were dragged into the war,” he said. “We tried hard to sort out things in a peaceful manner but so many people were arrested and it didn’t work.”

Osman joined a fighting group called the Liwa al Tawhid Brigade, which fought against both the Assad regime and Daesh.

For Osman, a Syrian Kurd, there were many battles to fight. Apart from defending the Syrian revolution, he wanted to protect the Syrian Kurds from Assad’s influences.

In one of the battles he fought in Aleppo, he witnessed co-operation between the Assad regime and the YPG. He could never come to terms with the YPG's tacit alliance with Assad, since he grew up witnessing his father and many other Kurds being tortured by the regime, scarring his childhood.

“There is a neighbourhood in Aleppo called Ashrafieh,” Osman said. “The arms coming out of police stations and warehouses were distributed among YPG members there. From that point onward, I knew that no Kurd would join the civil war. Why not? Because the YPG would prevent them. With the regime’s support, no Kurd will join the war.”

The tactic worked. The Syrian Kurds saw two forces — Daesh and the YPG — emerging out of the civil war. “The war got much worse. As Daesh got stronger, so did the YPG. The more Daesh’s horrific videos spread online, the stronger the YPG became on the ground,” Osman said.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the Baathist regime, led by Assad’s father, worked hand-in-glove with various extremist groups, including the PKK and Hezbollah. In the late 1970s, when the Baathist regime occupied Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, the PKK and several Shia militias ran training camps under Hafez al Assad’s supervision.

The camaraderie continues to this day. Posters of Bashar al Assad and the founder of the PKK, Abdullah Ocalan, hung next to each other on the streets of Aleppo’s Afrin district after Turkey started a military operation, Olive Branch, in late January to clear the YPG militants from the region. Ocalan has been serving a prison term in Turkey since 1999.

“YPG’s desire to turn Afrin into a second Qandil is a huge problem,” said Azad, whose father was born and raised in Afrin. “As for Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch, Turkey is a big and strong nation. Turkey wouldn’t allow Afrin to become a second Qandil (the PKK stronghold in Iraq) in front of its eyes.”

In 2013, he moved his family from Syria to Turkey. But he continued to fight. In 2014, both Osman and his son had a close shave with death. Their safe house in Aleppo came under a mortar attack by the regime forces, leaving them seriously injured.

The father and son came to Turkey for medical help and reunited with their family members. Osman saw his family “in a deplorable state.” “It was time for me to find a job, so they wouldn’t go hungry,” Osman said. “I started cleaning houses with my wife. Then I switched over to construction.”

“We were laying tiles during construction. My son lifted more because (he thought) his father was injured. I tried to lift more because my son was injured. We lived through very difficult days. But, most importantly, we could sleep easy in Turkey. There were no guns, no arrest. Assad’s missiles were gone, too,” he added.

Sido’s fondness for Osman has grown with time and separation.

"Nobody could separate us. Not the regime, not people's comments. On the contrary, we came closer to each other. Our love grew," Sido said.

Though the couple could not build a decisive Kurdish resistance against the Assad regime, they continue to fight everyday battles of existence from the periphery.

“There are many problems in life, but when you stand together with each other, there are no obstacles,” Sido said.'

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)