Robin Yassin-Kassab:

'Truth is always contested, especially in a war zone. That’s why people like Eliot Higgins are indispensable. He (and his Bellingcat organisation) geo-locate videos, cross-reference on the ground reports, and so on, in order to verify what’s happening. Within Syria, groups like the Violations Documentation Centre and the Syrian Network for Human Rights do very careful fact-checking. So the SNHCR’s statistics on civilian deaths in the conflict (finding 94% were caused by Assad and his allies up to October 2017) include only named and documented cases. The OPCW, UN bodies, and human rights organisations have released many reports finding Assad and his backers responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

So while truth is difficult to discern, it is still possible to discern it most of the time, and this is being done, those who pretend that it isn’t, or that no clear pattern emerges from the various reports, are therefore clouding the truth, whether deliberately or unwittingly.

From the start of the revolution in 2011 I aimed to inform and comment on actual events in Syria. Then it became more important to amplify Syrian voices and perspectives, because the English-language media in general was ignoring them. I didn’t pay much attention at first to the more extreme and blatant atrocity denial and propaganda. That was a mistake. The Assad regime, and Russia and Iran, have won the information or narrative war as surely as they’ve defeated the Syrian rebels. The aim of the Kremlin-Assad-Iran propaganda machine is not to create simply one alternative version of reality – because that version is a fiction, holes will inevitably be found in it – but many, so as to cloud the public sphere, so that nobody can be sure what’s happening. That’s why the Russian envoy to the UN claimed in the same speech that 1. there was no chemical atrocity in Douma, and 2. that the (non-existent?) atrocity was perpetrated by the rebels with help from western powers. Such stories are fed by the Kremlin onto western conspiracy theory websites, get picked up by alt-leftists and rightists, then by ignorant and lazy mainstream journalists, then become part of the accepted reality. So now, in order to discuss the latest Russian targeting of the White Helmets first responders, it’s necessary first to dispute endless conspiracy theories that the White Helmets are an al-Qaida front or a tool of western imperialism. Which is very convenient for the war criminals.

Reporters and authors should focus on actual facts first, then on human realities. Not on orientalist assumptions. They shouldn’t start with a narrative (like jihadis vs secularists, or Sunnis vs Shia, or ‘a re-run of Iraq’) and select or interpret facts to fit that narrative. Rather they should start with facts, then voices from people on the ground, and try to understand events on those terms. We as readers should stop relying on famous white correspondents who don’t speak local languages and who travel everywhere with regime minders. Newspapers and websites should take their fact-checking responsibilities far more seriously, and should publicly correct and apologise when their writers are proved wrong.

After seven years of repression and war, with the intervention of numerous foreign states and organisations, the geo-political aspect of the war dominates. In many respects the fate of Syria is now out of Syrian hands (including Assad’s). Yet the fundamental problem in Syria remains that millions of Syrians find the continuation of Assad rule intolerable, and Assad in turn finds the continuation of these opponents’ very existence in Syria intolerable. It was Assad’s original war on the people which birthed a series of regional and international conflicts. Without engaging with this reality, there will be no solution to the Syrian conflict. The remains of Syria will continue to throw out people, to inspire terrorism, and to provoke super-power sparring.

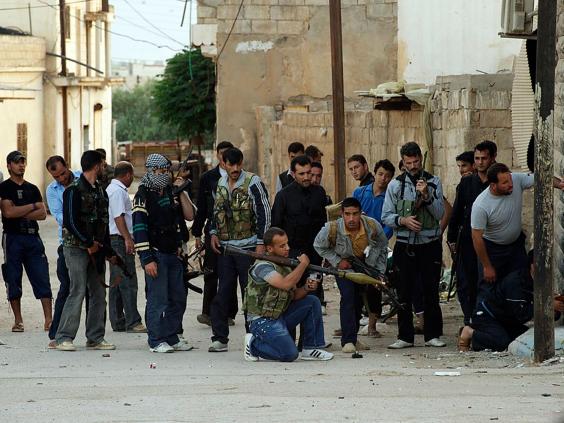

On some Fridays in 2011 and 2012 millions of Syrians went onto the streets to protest, even though they knew they would be shot at or arrested and tortured in the sweeps afterwards. They didn’t risk their lives, as some imagine, because they were incited or paid by the CIA, Mossad, or Saudi prince Bandar, but because they were immediately concerned by the failures of dictatorship. To see Syria only as a proxy war is to rob Syrians of their agency, and therefore points to a racist habit of thought.

Similar overgeneralisations lead to Idlib being described as ‘al-Qaida controlled’. Al-Qaida (or Nusra) is certainly present. So are various other Islamist and Free Army militias. So are local councils, women’s centres, free newspapers, trades unions, and people who regularly protest against Nusra.

Diane Abbott describes the Syrian revolution (which includes Christians) as mere “rag-tag jihadis”, and entirely ignores hundreds of democratic self-organised councils. Again, it’s the failure to see people, or even to want to see them. Only states and terrorists matter.

Islamophobic and racist overgeneralisations are as prominent on the left as on the right. in a nonsensical and reactionary binarism, ‘progressives’ are more likely to express solidarity with states – even fascist or imperialist states – than with people. As a result there is increasing red-brown convergence.

Analysis and engagement have been sacrificed in favour of (inaccurate) grand narratives and conspiracy theories. This way of seeing the world ends up in demonology. So for instance the triumvirate of evil – Israel, Saudi Arabia and the US – must be blamed for everything from the Arab Spring to ‘inventing ISIS’. (Nobody needs to make stuff up to criticise these states. They certainly commit terrible crimes. But this overgeneralisation leads to a picture of the world which is entirely false. Saudi Arabia, for instance, is scared of ISIS, has been repeatedly attacked by ISIS, funded mainly the Free Army in Syria – but also Jaish al-Islam which, while Salafist, ruthlessly eliminate ISIS and al-Qaeda cells in its area of control. Indeed Saudi Arabia is currently pursuing a fiercely anti-Islamist policy in the Arab world. It underwrote General Sisi’s coup against the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt).

The problem goes beyond the left. Brexit and Trump as well as Corbynism are symptoms of a larger cultural slide involving populism, conspiracism and the dominance of powerful fictions. A rigorous analysis of the phenomenon would have to take on board the role of social media and the growth of a ‘post-literate’ society in which people are simultaneously atomised (working at home, for instance, not meeting fellow workers every day) and strangely connected (to an international internet clique of similar opinion or interest). It may have to do with the collapse of traditional religion, then of its replacements (belief in progress, for instance), and therefore of the basic human need to fit ourselves into big stories.

We started the decade with grassroots revolutions. We’re heading to the end of the decade with these movements crushed on the ground and in the ideological sphere. Two pregnant quotes for our times:

Walter Benjamin – “Behind every rise of fascism is a failed revolution.”

Hannah Arendt – “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” '

Analysis and engagement have been sacrificed in favour of (inaccurate) grand narratives and conspiracy theories. This way of seeing the world ends up in demonology. So for instance the triumvirate of evil – Israel, Saudi Arabia and the US – must be blamed for everything from the Arab Spring to ‘inventing ISIS’. (Nobody needs to make stuff up to criticise these states. They certainly commit terrible crimes. But this overgeneralisation leads to a picture of the world which is entirely false. Saudi Arabia, for instance, is scared of ISIS, has been repeatedly attacked by ISIS, funded mainly the Free Army in Syria – but also Jaish al-Islam which, while Salafist, ruthlessly eliminate ISIS and al-Qaeda cells in its area of control. Indeed Saudi Arabia is currently pursuing a fiercely anti-Islamist policy in the Arab world. It underwrote General Sisi’s coup against the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt).

The problem goes beyond the left. Brexit and Trump as well as Corbynism are symptoms of a larger cultural slide involving populism, conspiracism and the dominance of powerful fictions. A rigorous analysis of the phenomenon would have to take on board the role of social media and the growth of a ‘post-literate’ society in which people are simultaneously atomised (working at home, for instance, not meeting fellow workers every day) and strangely connected (to an international internet clique of similar opinion or interest). It may have to do with the collapse of traditional religion, then of its replacements (belief in progress, for instance), and therefore of the basic human need to fit ourselves into big stories.

We started the decade with grassroots revolutions. We’re heading to the end of the decade with these movements crushed on the ground and in the ideological sphere. Two pregnant quotes for our times:

Walter Benjamin – “Behind every rise of fascism is a failed revolution.”

Hannah Arendt – “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” '